Source: Al Jazeera

Friday 10 February 2023 10:32:59

Why Is It so Hard to Predict Earthquakes?

An earthquake, in the simplest terms, is when the earth shakes.

Did you know that there are hundreds of earthquakes every single day, not always strong enough for us to notice them? Then there are some massive ones that cause huge damage and loss of life. These terrifying events raise many questions; here are some answers.

Whose ‘fault’ is it when an earthquake happens?

The surface of the Earth is made of kilometres of hard rock broken into a puzzle of moving pieces called tectonic plates, which sit on a sea of hot, liquid rock that rolls as it cools, pushing the plates around. Earthquakes and volcanoes occur on the surface where they meet.

Plates are always technically in motion but are usually locked together, building stress until something underground snaps, freeing them to slide along known lines of fractured rock called faults, that can run for kilometres.

When the pressure suddenly releases and the plate moves, energy explodes into the surrounding rock.

How do you know how strong an earthquake was?

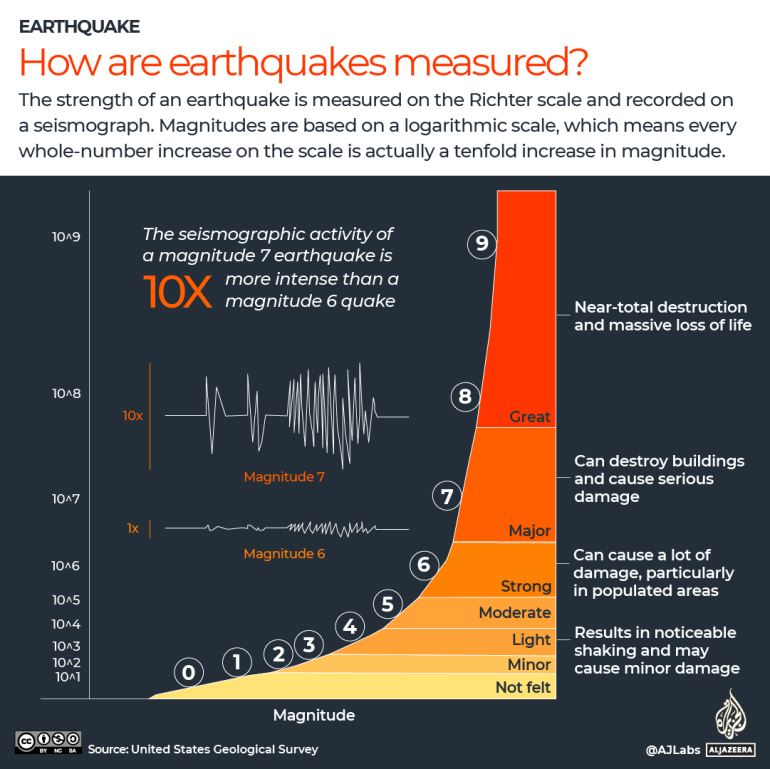

Scientists use seismographs, which used to be wiggling needles that record the ground’s shakes, but now the equipment is all digital. There is a global network of these, as well as local and regional networks, and much of the data is open-source and automatically connected. By combining at least three measurements, systems can map the location, duration and size of an earthquake with precision. Finally, there are a few different measurements of earthquakes, but the most widely used magnitude refers to the overall size, and each step is 10 times greater than the step below.

In addition to seismometers, geologists and seismologists have a variety of tools to collect data about the Earth’s crust’s movements. GPS-connected sensors are placed near seismically active sites to measure movement on the surface. Satellite photos taken before and after an event can be compared pixel-by-pixel. A satellite-based radar called InSAR is one of the most important tools for sensing how the Earth’s surface changes: it reflects beams of radiowaves from orbit over sweeps of the Earth, and a process called interferometry records changes in surface height accurately to millimetres. The satellite passes twice to see what has changed on the ground. Machine learning techniques are also now being tried on large datasets to find signals faster than humans can.

Can one earthquake cause another?

Though earthquakes are known to trigger other earthquakes, how that happens is a territory of fierce discussion among scientists. Earthquakes expose two paradoxes about how humans understand the natural world: they happen over timespans longer than human experience and occur at depths far beyond people’s ability to observe directly.

Scientists manage this by making models and calculating probabilities. After an earthquake, scientists look at the data to better understand what might happen next. “We have to put a stethoscope” on the Earth, said Harold Tobin, professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Washington, “to determine what’s happening down there.